Second Polish Republic

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

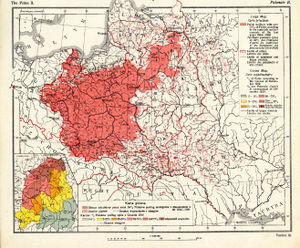

The Second Polish Republic, Second Commonwealth of Poland or interwar Poland (Polish: II Rzeczpospolita, lit. "Second Republic"), officially known as the Republic of Poland (Polish: Rzeczpospolita Polska), was the independent Polish state that existed between the two world wars: from the creation of an independent Poland in the aftermath of World War I, to the invasion of Poland in 1939 by Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union, and the Slovak Republic, which marked the beginning of World War II.

When the borders of the state were fixed in 1922 after several regional conflicts, the Republic bordered Czechoslovakia, Germany, Free City of Danzig, Lithuania, Latvia, Romania, and the Soviet Union, plus a tiny strip of the coastline of the Baltic Sea, around the city of Gdynia. Furthermore, in the period March 1939 – August 1939, Poland bordered then-Hungarian Carpathian Ruthenia. It had an area of 388 634 km² (sixth largest in Europe, in the fall of 1938, after the annexation of Zaolzie, the area grew to 389,720 km².), and 27.2 million inhabitants according to the 1921 census. In 1939, just before the outbreak of World War II, it had an estimated 35.1 million inhabitants. Almost a third of these were of minority groups: 13.9% Ukrainians; 3.1% Belarusians; 8.6% Jews; 2.3% Germans; and 3.4% percent Czechs, Lithuanians and Russians).

The Second Polish Republic is often associated with times of great adversity, of troubles and of triumph. Having to deal with the economic difficulties and destruction of World War I, followed by the Soviet invasion during the Polish–Soviet War, and then increasingly hostile neighbors such as Nazi Germany, the Republic managed not only to endure, but to expand. Lacking an overseas empire (see: Maritime and Colonial League), Poland nevertheless maintained a level of economic development and prosperity comparable to that of the West. The cultural hubs of Warsaw, Kraków, Poznań, Wilno and Lwów raised themselves to the level of major European cities. They were also the sites of internationally acclaimed universities and other institutions of higher education. By 1939 the Republic was becoming a stable country in politics and economics.[1]

Contents |

History

Timeline (1918–1939)

- October 31, 1918–1919: Polish-Ukrainian War.

- November 11, 1918: Independence; Warsaw was free.

- December 27, 1918–1919 Greater Poland Uprising – against Germany

- 1918–1939: Border conflicts between Poland and Czechoslovakia.

- January 23 – 30, 1919: Polish–Czechoslovak War.

- January 26, 1919: Elections to the Sejm.

- June 28, 1919: Treaty of Versailles (Articles 87–93) and Little Treaty of Versailles, establish Poland as a sovereign and independent state on the international arena.

- 1919–1921: Polish-Soviet War, Miracle of the Vistula, Treaty of Riga.

- 1920: Polish-Lithuanian War.

- 1919 - 1921 Uprisings in Silesia, Silesian Uprisings.

- July 15, 1920: Agrarian Reform.

- March 17, 1921: March Constitution.

- 1921: alliances with France, Romania.

- March 24, 1922: annexation of Vilnius Region from Lithuania

- November 2 – 12, 1922: Elections to the Sejm and to the Senat.

- President Gabriel Narutowicz, and his assassination (December 16, 1922).

- 1924: Wladyslaw Grabski Government. Bank Polski. Monetary reform 1924 in Poland.

- President Stanisław Wojciechowski – December 20, 1922, to Zamach majowy.

- May 12 – 14, 1926: Coup of May – Zamach majowy, 1926, May, Józef Piłsudski coup d'état (May Coup). beginning of Sanacja government.

- Roman Dmowski, Obóz Wielkiej Polski (4 December 1926), Endecja.

- 1928: Piłsudski's nonpartisan Bloc for Cooperation with the Government.

- November 16, 1930: Polish legislative election.

- July 25, 1932: non-aggression pact with Soviet Union

- January 26, 1934: non-aggression pact with Germany

- April 23, 1935: April Constitution

- May 12, 1935: death of Józef Piłsudski

- 1930s: Gdynia, Centralny Okreg Przemyslowy (1936), Eugeniusz Kwiatkowski

- February 2, 1937: creation of the Obóz Zjednoczenia Narodowego political party".[2].

- October 1938: annexation of Zaolzie, Górna Orawa, Jaworzyna from Czechoslovakia

- January 2, 1939: death of Roman Dmowski

- March 31, 1939: military guarantees from United Kingdom and France

- August 23, 1939: non-aggression pact between Soviet Union and Germany: Ribbentrop-Molotow Pact with a secret military alliance protocol targeting Poland (among several other countries)

- August 25, 1939: alliance between Poland and United Kingdom

- September 1 – October 6, 1939: Invasion of Poland

The beginnings

Occupied by German and Austro-Hungarian armies in the summer of 1915, the formerly Russian-ruled part of what was considered Poland was proposed to become a German puppet state by the occupying powers on November 5, 1916, with a governing Council of State and (from October 15, 1917) a Regency Council (Rada Regencyjna Królestwa Polskiego) to administer the country under German auspices (see also Mitteleuropa) pending the election of a king.

Shortly before the end of World War I, on October 7, 1918, the Regency Council dissolved the Council of State and announced its intention to restore Polish independence. With the notable exception of the Marxist-oriented Social Democratic Party of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania (SDKPiL), most political parties supported this move. On October 23 the Council appointed a new government under Józef Swierzynski and began conscription into the Polish Army. On November 5, in Lublin, the first Soviet of Delegates was created. On November 6 the Communists announced the creation of a Republic of Tarnobrzeg. The same day, a Provisional People's Government of the Republic of Poland was created under the Socialist, Ignacy Daszynski.

On November 10, Józef Piłsudski, newly freed from imprisonment by the German authorities at Magdeburg, returned to Warsaw. Next day, due to his popularity and support from most political parties, the Regency Council appointed Piłsudski Commander in Chief of the Polish Armed Forces. On November 14 the Council dissolved itself and transferred all its authority to Piłsudski as Chief of State (Naczelnik Państwa).

Centers of government that were created in Galicia (formerly Austrian-ruled southern Poland) included a National Council of the Principality of Cieszyn (created in November 1918) and a Polish Liquidation Committee (created on October 28). Soon afterward, conflict broke out in Lwów between forces of the Military Committee of Ukrainians and the Polish irregular units of students and children, known as Lwów Eaglets, who were later supported by the Polish Army.

After consultation with Pilsudski, Daszynski's government dissolved itself and a new government was created under Jędrzej Moraczewski.

World War II

The beginning of the Second World War put an end to the Second Polish Republic. The "Invasion of Poland" campaign began 1 September 1939, one week after the signing of the secret Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, and ended 6 October 1939, with Germany and the Soviet Union occupying the entirety of Poland (with the exception of the area of Wilno, which was annexed by Lithuania). Poland did not surrender, but continued as Polish Government in Exile and the Polish Underground State.

Politics and government

| Part of a series on |

|

| Polish statehood |

| Poland |

| Kingdom of the Piasts

Kingdom of the Jagiellons Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth Partitions of Poland Kingdom of Galicia Duchy of Warsaw Kingdom of Poland (Congress Poland) Grand Duchy of Posen Grand Duchy of Cracow Second Polish Republic Polish Underground State People's Republic of Poland Third Polish Republic |

| Poland portal |

The Second Polish Republic was a parliamentary democracy from 1919 to 1926, with the President having limited powers. The Parliament elected him, and he could appoint the Prime Minister and the government with the Sejm's (lower house's) approval, but he could only dissolve the Sejm with the Senate's consent. Moreover, his power to pass decrees was limited by the requirement that the Prime Minister and the appropriate other Minister had to verify his decrees with their signatures. The major political parties at this time were the National Democrats and other right-wing groups, the various Peasant Parties, the Social Democrats, and the ethnic minority political groups (mainly the Jewish and German ones). Frequently changing governments and other negative publicity which the democratic politicians received (such as accusations of corruption), made them increasingly unpopular. Major democratic politicians at this time included Wincenty Witos (Prime Minister three times) and Roman Dmowski. By contrast, Marshal Józef Pilsudski led an intentionally modest life, writing historical books for a living. After he took power by a military coup in May 1926, he emphasized that he wanted to heal the Polish society and politics of excessive partisan politics. His regime, accordingly, was called Sanacja in Polish. The 1928 parliamentary elections were still considered free and fair, although the pro-Pilsudski Nonpartisan Bloc for Collaboration with the Government won them. The following three parliamentary elections (in 1930, 1935 and 1938) were manipulated, and thus the pro-government party won huge majorities in them. Pilsudski died just after an authoritarian constitution was approved in the spring of 1935. During the last four years of the Second Polish Republic, the major politicians included President Ignacy Moscicki, Foreign Minister Józef Beck and the Commander-in-Chief of the Polish army, Edward Rydz-Smigly (see, for example, Norman Davies, Poland: God's Playground (some editions since the 1980's), Kalervo Hovi, A History of Poland/Puolan historia, published in Finland in 1993, and the English-language Wikipedia articles on the Polish parliamentary elections between 1919 and 1938).

Chief of State

- Józef Piłsudski – 22 November 1918 – 9 December 1922

Presidents

- Gabriel Narutowicz – 9 December 1922 – 16 December 1922

- Stanisław Wojciechowski – 20 December 1922 – 14 May 1926

- Ignacy Mościcki – 1 June 1926 – 30 September 1939

- Bolesław Wieniawa-Długoszowski – 1 October 1939

Prime ministers

- Jędrzej Moraczewski – 18 November 1918 – 16 January 1919

- Ignacy Paderewski – 18 January 1919 – 27 November 1919

- Leopold Skulski – 13 December 1919 – 9 June 1920

- Władysław Grabski – 27 June 1920 – 24 July 1920

- Wincenty Witos – 24 July 1920 – 13 September 1921

- Antoni Ponikowski – 19 September 1921 – 5 March 1922

- Antoni Ponikowski – 10 March 1922 – 6 June 1922

- Artur Śliwiński – 28 June 1922 – 7 July 1922

- Wojciech Korfanty – 14 July 1922 – 31 July 1922

- Julian Nowak – 31 July 1922 – 14 December 1922

- Władysław Sikorski – 16 December 1922 – 26 May 1923

- Wincenty Witos – 28 May 1923 – 14 December 1923

- Władysław Grabski – 19 December 1923 – 14 November 1925

- Aleksander Skrzyński – 20 November 1925 – 5 May 1926

- Wincenty Witos – 10 May 1926 – 14 May 1926

- Kazimierz Bartel – 15 May 1926 – 4 June 1926

- Kazimierz Bartel – 8 June 1926 – 24 September 1926

- Kazimierz Bartel – 27 September 1926 – 30 September 1926

- Józef Piłsudski – 2 October 1926 – 27 June 1928

- Kazimierz Bartel – 27 June 1928 – 13 April 1929

- Kazimierz Świtalski – 14 April 1929 – 7 December 1929

- Kazimierz Bartel – 29 December 1929 – 15 March 1930

- Walery Sławek – 29 March 1930 – 23 August 1930

- Józef Piłsudski – 25 August 1930 – 4 December 1930

- Walery Sławek – 4 December 1930 – 26 May 1931

- Aleksander Prystor – 27 May 1931 – 9 May 1933

- Janusz Jędrzejewicz – 10 May 1933 – 13 May 1934

- Leon Kozłowski – 15 May 1934 – 28 March 1935

- Walery Sławek – 28 March 1935 – 12 October 1935

- Marian Zyndram-Kościałkowski – 13 October 1935 – 15 May 1936

- Felicjan Sławoj Składkowski – 15 May 1936 – 30 September 1939

Economy

After regaining her independence Poland was faced with major economic difficulties. In addition to the devastation wrought by World War I, the exploitation of the Polish economy by the German and Russian occupying powers, and the sabotage performed by retreating armies, the new republic was faced with the task of economically unifying disparate economic regions, which had previously been part of different countries.[3]Within the borders of the Republic were the remnants of three different economic systems, with five different currencies (the German mark, the Russian ruble, the Austrian crown, the Polish marka and the Ost-rubel)[3] and with little or no direct infrastructural links. The situation was so bad that neighboring industrial centers as well as major cities lacked direct railroad links, because they had been parts of different occupying nations. For example, in the 1920s there was no direct railroad connection between Warsaw and Kraków, and the line was not completed until 1934.

On top of this was the massive destruction left after both World War I and the Polish Soviet War. There was also a great economic disparity between the eastern (commonly called Poland B) and western (called Poland A) parts of the country, with the western half, especially areas that had belonged to the German Empire being much more developed and prosperous. Frequent border closures and tariff wars (especially with Nazi Germany) also had negative economic impacts on Poland.

Despite these problems Poland managed in the interwar period to achieve a state of economic prosperity on par with Western Europe. In 1924 prime minister and economic minister Władysław Grabski introduced the złoty as a single common currency for Poland, which remained one of the most stable currencies of Central Europe. The currency helped Poland to bring under control the massive hyperinflation, the only country in Europe which was able to do this without foreign loans or aid (see also Polish marka).

The basis of Poland's relative prosperity were the mass economic development plans which oversaw the building of three key infrastructural elements. The first was the establishment of the Gdynia seaport, which allowed Poland to completely bypass Gdańsk (which was under heavy German pressure to boycott Polish coal exports). The second was construction of the 500-kilometer rail connection between Upper Silesia and Gdynia, called Polish Coal Trunk-Line, which served freight trains with coal. The third was the creation of a central industrial district, named the COP – Central Industrial Region (Centralny Okręg Przemysłowy). Unfortunately, these developments were interrupted and largely destroyed by the German and Soviet invasion and the start of World War II.[4]

Interbellum Poland was also the country with numerous social problems. Unemployment was high, and poverty was widespread, which resulted in several cases of social unrest, such as 1923 Kraków riot, and 1937 peasant strike in Poland.

Railways

According to the 1939 Statistical Yearbook of Poland, total length of railways of Poland (as for December 31, 1937) was 20 118 kilometers. Rail density was 5.2 km. per 100 km2. Railways were very dense in western part of the country, and in the east, especially Polesie, rail was non-existent in some counties. During the interbellum period, Polish government constructed several new lines, mainly in central part of the country (see also Polish State Railroads Summer 1939).

Demographics

Poland was historically a nation of many nationalities, with large Jewish and Ukrainian minorities. This was especially true after she regained her independence in the wake of World War I, in 1918. The census of 1921 allocates 30.8% of the population in the minority.[5] This was further exacerbated with the Polish victory in the Polish-Soviet War, and the large territorial gains made by Poland as a consequence. According to the 1931 Polish Census (as cited by Norman Davies[6]), 68.9% of the population was Polish, 13.9% were Ukrainians, 8.6% Jews, 3.1% Belarusians, 2.3% Germans and 2.8% - others, including Lithuanians, Czechs and Armenians. Also, there were smaller communities of Russians, and Gypsies. The situation of minorities was a very touchy subject. The government oppressed them, and such events, as Pacification of Ukrainians in Eastern Galicia (1930), echoed across the world.

Poland was also a nation of many religions. In 1921 16,057,229 Poles (approx. 62.5%) were Roman (Latin) Catholics, 3,031,057 citizens of Poland (approx. 11.8%) were Eastern Rite Catholics (mostly Ukrainian Greek Catholics and Armenian Rite Catholics), 2,815,817 (approx. 10.95%) were Greek Orthodox, 2,771,949 (approx. 10.8%) were Jewish, and 940,232 (approx. 3.7%) were Protestants (mostly Lutheran Evangelical).[7] By 1931 Poland had the second largest Jewish population in the world, with one-fifth of all the world's Jews residing within Poland's borders (approx. 3,136,000).[5]

Population

| Date | Population | Percentage of rural population |

Population density (per km²) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30 September 1921 (census) | 27,177,000 | 75,4% | 69,9 |

| 9 December 1931 (census) | 32,348,000 | 72,6% | 82,6 |

| 31 December 1938 (estimate) | 34,849,000 | 70% | 89,7 |

- Largest cities in early 1939:

- Warsaw – 1,289,000

- Łódź – 672,000

- Lwów – 318,000

- Poznań – 272,000

- Kraków – 259,000

- Wilno – 209,000

- Bydgoszcz – 141,000

- Częstochowa – 138,000

- Katowice – 134,000

- Sosnowiec – 130,000

- Lublin – 122,000

- Gdynia – 120,000

- Chorzów – 110,000

- Białystok – 107,000

Administrative division

The Administrative division of Second Polish Republic was based on the three tier system. On the lowest rung were the gminy, which were little more than local town and village governments. These were then grouped together into powiaty which were then arranged into wojewodstwa.

| Polish voivodeships in the interbellum (data as per April 1, 1937) |

|||||

| car plates (since 1937) |

Voivodeship Separate city |

Capital | Area in 1,000 km² (1930) |

Population in 1,000 (1931) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 00–19 | City of Warsaw | Warsaw | 0.14 | 1,179.5 | |

| 85–89 | warszawskie | Warsaw | 31.7 | 2,460.9 | |

| 20–24 | białostockie | Białystok | 26.0 | 1,263.3 | |

| 25–29 | kieleckie | Kielce | 22.2 | 2,671.0 | |

| 30–34 | krakowskie | Kraków | 17.6 | 2,300.1 | |

| 35–39 | lubelskie | Lublin | 26.6 | 2,116.2 | |

| 40–44 | lwowskie | Lwów | 28.4 | 3,126.3 | |

| 45–49 | łódzkie | Łódź | 20.4 | 2,650.1 | |

| 50–54 | nowogródzkie | Nowogródek | 23.0 | 1,057.2 | |

| 55–59 | poleskie | Brześć nad Bugiem | 36.7 | 1,132.2 | |

| 60–64 | pomorskie | Toruń | 25.7 | 1,884.4 | |

| 65–69 | poznańskie | Poznań | 28.1 | 2,339.6 | |

| 70–74 | stanisławowskie | Stanisławów | 16.9 | 1,480.3 | |

| 75–79 | śląskie | Katowice | 5.1 | 1,533.5 | |

| 80–84 | tarnopolskie | Tarnopol | 16.5 | 1,600.4 | |

| 90–94 | wileńskie | Wilno | 29.0 | 1,276.0 | |

| 95–99 | wołyńskie | Łuck | 35.7 | 2,085.6 | |

On April 1, 1938, borders of several western and central Voivodeships changed considerably. For more information, see Territorial changes of Polish Voivodeships on April 1, 1938.

Geography of the Second Polish Republic

Second Polish Republic was mainly flat, with average elevation of 223 meters above sea level (after World War II and its border changes, the average elevation of Poland decreased to 173 meters). Only 13% of territory, along the southern border, was higher than 300 meters. The highest elevation was Mount Rysy, which rises 2,499 meters in the Tatra Range of the Carpathians, 95 kilometers south of Kraków. Between October 1938 and September 1939, the highest elevation was Lodowy Szczyt (known in the Slovakian language as Ľadový štít), which rises 2,627 meters above sea level. The biggest lake was Lake Narach.

Country's total area, after annexation of Zaolzie, was 389,720 km²., it extended 903 kilometers from north to south and 894 kilometers from east to west. On January 1, 1938, total length of boundaries was 5 529 km., including:

- 140 kilometers of coastline (out of which 71 kilometers were made by the Hel Peninsula),

- 1412 kilometers with Soviet Union,

- 948 kilometers with Czechoslovakia (until 1938),

- 1912 kilometers with Germany (together with East Prussia),

- 1081 kilometers with other countries (Lithuania, Romania, Latvia, Danzig).

Among major cities of the Second Polish Republic, the warmest yearly average temperature was in Kraków (9.1 C in 1938) and the coldest in Wilno (7.6 C in 1938).

Extreme points

- Northernmost point: N55*51'8,45" (N55,852250*); Przeświata River in Somino, located in the Braslaw county of the Wilno Voivodeship

- Southernmost point: N47*43'31,8" (N47,725492*); spring of Manczin River located in the Kosów county of the Stanisławów Voivodeship

- Easternmost point: E28*21'44,3" (E28,362371*); Spasibiorki (near railway to Połock) located in the Dzisna county of the Wilno Voivodeship

- Westernmost point: E15*47'12,4" (E15,786773*); Mukocinek near Warta River and Meszyn Lake located in the Międzychód county of the Poznań Voivodeship

Drainage

Almost 75% of the territory of interbellum Poland was drained northward into the Baltic Sea by the Vistula (total area of drainage basin of the Vistula within boundaries of the Second Polish Republic was 180 300 km².), the Niemen (51 600 km².), the Odra (46 700 km².) and the Daugava (10 400 km².). The remaining part of the country was drained southward, into the Black Sea, by the rivers that drain into the Dnieper (Pripyat, Horyn and Styr, all together 61 500 km².) as well as Dniester (41 400 km².)

See also

- 1939 in Poland

References

- ↑ The End, TIME Magazine, October 2, 1939

- ↑ Seidner, Stanley S. (1975). "The Camp of National Unity: An Experiment in Domestic Consolidation". The Polish Review 20 (2–3): 231–236.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Nikolaus Wolf, "Path dependent border effects: the case of Poland's reunification (1918-1939)", Explorations in Economic History, 42, 2005, pgs. 414-438

- ↑ Atlas Historii Polski, Demart Sp, 2004, ISBN 83-89239-89-2

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Joseph Marcus, Social and Political History of the Jews in Poland, 1919–1939, Mouton Publishing, 1983, ISBN 90-279-3239-5, Google Books, p. 17

- ↑ Norman Davies, God's Playground, Columbia University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-231-12819-3, Google Print, p.299

- ↑ Powszechny Spis Ludnosci r. 1921

External links

- Borders, Google Earth